In July 1938, in a speech to farmers at Kettering, Neville Chamberlain said there was “no need to encourage the greatest output of food at home because ample supplies would continue from overseas in the event of war.” Secretly, however, as early as 1933, plans had already been made to control prices, wages and profits in the event of a major war. The government was building on experiences gained in the second half of the Great War, and their aims were two-fold: to increase the fertility of the land by maintaining livestock production and planning to plough up grassland immediately war was declared, so that the supply of human and animal foodstuffs could be increased very rapidly. It was also proposed that War Emergency Committees be set up to oversee wartime needs. Local people had been selected to run these committees, though they were not aware of it at the time.

In 1936, therefore grants had become available for drainage and subsidies were introduced for fertiliser and this led in the war years to a doubling of the quantity of potash and phosphate applied to the fields. A wheat subsidy which was already in place had been extended to barley and oats. By 1939, there was also a payment of £2 an acre for every acre ploughed up between May and September 1939. The aim was to have two million acres of grassland ploughed in time for the 1940 harvest.

Key occupations were to be reserved so there was an adequate labour force and preparations were in place to recruit for the Women’s Land Army, which had been an important force even in the First World War. Lady Denman, whom we have met in her guise as organiser of the WI, was put in charge of organising and recruiting for the WLA and this she went about with her usual ferocious tenacity. She was convinced of the importance of her work, as during the First World War the country had had only three weeks’ supply of food left when the harvest failed in 1917. She was determined this would not happen if she could help it. “The Land Army fights in the fields. It is in the fields of Britain that the most critical battle of the war may well be fought and won,” she declared in 1939. The WLA was formed on 1st June 1939 and two groups of land girls were trained and ready for work by the time war was declared in September 1939.

Life in the Elsfield during the war years is described in two very different ways. One is by Ann Paton, who gives a child’s eye view of the times, while the second is an account by Helena Deneke written for an Oxfordshire Women’s Institute competition. These two main sources are supplemented by the recollections of Arthur Phipps and George Hambidge.

Anne Paton’s account

Anne offers a direct way into the everyday activities, the sounds, smells and colour of her life in Elsfield acutely observed and dedicated to her grandparents. She was the eldest of six children, who lived at School Cottage with their parents Bessie and Ben Jones. Her grandparents lived in one of the thatched cottages at the other end of the village and Anne and her sister spent a good deal of time there. Her grandparents’ cottage, rented from Mr Willis at Forest Farm, was small. It had two bedrooms, a sitting room, a scullery and an outside toilet where the coal and wood were stored. It was very dark so they had to use a candle and as it was not a water closet it was, as Anne ruefully comments, rather smelly. There were some very good things about the place, however.

“My grandparents had a big garden and a good sized vegetable patch which had everything you could grow: flowers, plums, apples, redcurrants, blackcurrants, gooseberries and strawberries. My grandma made jam and bottled fruit. Can you imagine the smell in the kitchen? I would love to open the larder just to sniff, it was so good. Jams, pickles, meat, mint cakes and spices. It was just my idea of heaven, so mouth-watering.”

Living in the little cottage were not only her grandparents but her great grandma Hallett and Anne provides a graphic picture of Nan Hallett getting ready for bed:

“I often stayed the night with my grandparents. I loved this. My sister and I would enjoy an evening by the fireside when it was winter. Our supper was a cup of cocoa, very dark cocoa, and a biscuit, while the older ones had bread and a slither of cheese. My Nan Hallett used to say, ‘By gum, I enjoyed that!’ No-one stayed up later than ten o’clock. We were packed off to bed at 9.30. We had to go upstairs by candle light which was a bit spooky. Nan’s bed was a big bed with a brass head with a deep, deep mattress with large pillows and a large eiderdown. My Nan always had a stone hot water bottle in the bed, wrapped around it was her night gown. She felt the cold and always wore a shawl. The water in the bottle was for her morning wash. Great Gran would come to bed, puffing up the stairs with her candle to light her way, flickering and causing shadows to dance on the walls. With childish fear, my sister Pat and I would dive under the covers as quickly as possible. Great Gran would then start undressing. Knitted jumper and long black skirt, always a pinny over her clothes, beautiful white slip and then her stays as she called them in which she had pockets to carry her money on a journey. These were boned and laced to pull her in and keep her warm. Underneath she wore ‘coms’ (combinations) an all in one vest and pants to the ankle. What an ordeal that was! After this a beautiful nightgown pulled over her head with a big sigh of relief. Her next duty was her long white hair and when she had finished she would take the loose hair from her comb and twist it round her finger, then pop it in a pot.”

The Phipps family outside 2 Terraced Cottages

Anne then goes on to describe her Nan’s chest of drawers. One drawer was full of “every article under the sun”: lozenges, hankies, chocolate, soap, hairpins, scent, lavender bags “and the odd packet of cigarettes – Players or Woodbines – which she had been given. She would sometimes keep these and wrap them up as presents for some of the men at Christmas.” Both Nan Hallett and her daughter Mrs Phipps worked in the kitchen at the Manor for Lady Tweedsmuir, and though loving towards the children, Nan Hallett was not so nice to her son-in-law who smoked a pipe, which she disliked.

Grandpa Phipps worked on the farm and would walk to work everyday, hands behind his back and his boots ringing on the road from the steel tips on his boots. He always seemed deep in thought but the children knew he carried peppermints with him. “We would tap on his shoulder and say, ‘Peppy, Gramp, peppy!’ and he would give us one. He only had a few a week which was his ration so really we were a bit naughty to ask,” Anne explained. The cooking for his dinner was done on a range open fire and in the oven was a rice pudding or a pie. After this he would smoke a pipe and then set off back to work. He walked up and down six times a day to work. “He had some nasty jobs to do like emptying the toilet bucket in a hole dug by him,” Anne added.

It was less idyllic at home, where her parents struggled to bring up their six children with very little money. Being the eldest, Anne was the one to be kept off school to help her mother when she was pregnant and when the babies were little. She helped with the washing which was a heavy job made doubly difficult for Bessie, who suffered so badly from ecxema that by the end of wash day her hands were cracked and bleeding. On a Monday morning, they would fill the copper with water fetched from a pump shared by three houses, bucket by bucket. Once filled, it was then lit by wood and paper, then coal to heat the water. It was Anne’s job to turn the mangle after rinsing the clothes in cold water, then she would hang out the washing.

Bessie, like many of the people of Elsfield, made very good use of her bicycle. As a girl on leaving school, she had cycled to Woodstock to the glove factory and, when her children were little, she fetched the shopping from Marston on her bike.

For Anne’s parents, it was always a struggle to make ends meet. Sometimes they were in debt to the grocer but Bessie’s sister Joan was in the Land Army based at Church Farm so she could sometimes provide them with eggs and milk and occasionally meat. At one time or another, they kept pigs, geese, chickens and ducks and once, Ben tried breeding rabbits but this was a disappointment. His garden was his pride and joy but he would never sell anything though his vegetables and flowers were the best in the village.

Fuel was also a problem, as not only had School Cottage, with its stone floors, to be heated but so did all the water they needed for washing. “In the winter we used to be outside sawing wood by hurricane lamp and it was hard work. My feet would be frozen and I had to jump up and down to keep warm,” says Anne. Coal was expensive and in short supply and Bessie could only afford a little at a time so wood was kept for the copper so they could have a bath on Sunday. “The water was ladled in and out by bucket and put into the tin bath. Very hard work and we had to take turns in the water, small ones first. Being older I hated this,” was Anne’s comment.

When war broke out, Ben joined the RAF and drove a ‘Queen Mary’, a big vehicle which was for carrying aircraft and which could sometimes be seen parked outside the school.

Anne describes the free time she had with affection:

“Our days off school were happy ones and sometimes my Auntie Audrey[1] would spend quite a bit of time with us. When her father was hay making, we would take his tea to him in a basket with sandwiches and cake and a bottle of cold tea. My Nan would put enough in for us too. We used to love this. After tea, we would help the men load the hay cart and afterwards we would stroke the horse before riding on the cart home.”

She and Audrey also liked to play in Woodeaton Wood, which was the nearest woodland to her grandparents’ house.

“It had a cart track through the middle like a cross road. In the summer it was grown over with a carpet of lush green grass. You could not see the other end so we would skip singing “The wonderful wizard of Oz”. This was a special place as there are lots of wild flowers in there – orchids, primroses, dog roses, bluebells , violets and many trees with honeysuckle growing up the trunks. One day we were walking back up the field when I saw a piece of rope or so I thought but it was a snake. My Auntie shouted just in time as I was just about to pick it up. I was so scared!”

Audrey Phipps as an adult

The war did impinge on one occasion when Anne was returning from the farm with a jug of milk. She had reached the church when she heard a rumbling noise. She jumped up on the bank as a convoy of tanks went past on their way to the Otmoor bombing range. “I could hardly breathe as I thought the Germans had arrived and I ran home screaming to my mother,” said Anne.

Anne was only seven when that happened but later, when the war was over and normal life was beginning to be resumed she joined the G.F.S – the Girls’ Friendly Society. They met at the Vicarage and were taught to crochet and embroider and said prayers and sang. It was a quiet and peaceful way of life. “We would all go to Sunday school and Church. Sunday evenings we would get together with another family, the Maltbys, and go for walks through the fields with our dogs and catch up on the gossip”.

According to Anne’s account of her life in Elsfield, the major event of the year was Christmas. It demonstrates how the difficulties of life in wartime and the lack of money, though it must have been a cause of concern for the adults, did not diminish the pleasure the children experienced.

“There was no money to spare so when my Dad finished work he would come home at dinner time on Christmas Eve, then my mother would go shopping. It was a long job and I will never know how she carried it all on her bike. As it grew dark we would make tea and wait till mum came home. Everyone was so excited. It was only then did the cake get iced and presents wrapped up when the little ones were in bed. We always had a real tree. My Dad saw to this and then he would dress it with real candles and cotton wool and barley sugar sticks and little odds and ends. It was so pretty. All the decorations were made by hand, we made our paper chains from pretty paper or sometimes plain white paper until we could afford to buy some real ones. Our house smelled so good with all the cooking preparation. My Nans would have saved a pudding from the year before and it was given as a present or some tinned fruit, which was hard to get. Anyway, Christmas Day was great being a big family. My Dad was good at making wooden toys for us so we were lucky.”

The customs from earlier in the century were still carried on. On Christmas Eve all the boys and girls in the village would gather by the school and start carol singing. The most important call was at the Manor House, where Lady Tweedsmuir had gathered all her family. The group of children would go in and sing to them all. The carol singers were given food and a warm drink to take them on their way and when they reached the end of the village it was late so they would walk back just in time for bed.

[1] Audrey Phipps, who married George Hambidge.

Miss Deneke’s Account of the War Years

Miss Deneke’s account of the war years is factual and detailed and shows how the world events which were unfolding impacted on village life.

She first of all sketches out the recent changes in the landscape: towards Kidlington there is a new granary for drying corn erected for wartime needs. A thick column of smoke rises from the ground near Bletchington because of the growth of the cement works and Woodeaton Manor has been taken over by the BBC’s pay department. They have built offices in the stables and have adapted the house. “The BBC has evacuated itself to Oxfordshire,” she says.

She gives a brief description of Elsfield in 1939: There are 25 cottages, a school and six more sizeable houses: The Manor, Hill Farm, Church Farm, the Vicarage, Home Farm and Forest Farm. “A half decayed huge tree opposite the Manor serves as a trysting place and a notice board”. This is long gone though the cottage beside where it used to stand is called ‘Tree Cottage’.

The postal service is affected. Mrs Hambidge has run the post office and shop but “owing to failing health and to regulations since the war demanding too large a number of registered customers Mrs Hambidge has had to forego her licence”. (Every family had to be registered with a supplier of groceries and Mrs Hambidge must have felt unable to cope with all the extra paperwork entailed.) The Post Office has been closed down and the post is deposited in Beckley. Mrs Colwell bicycles to fetch letters and delivers to Stow Wood and Elsfield.

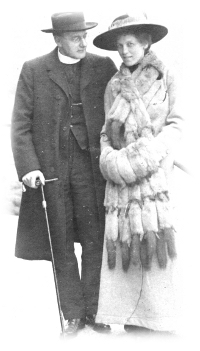

Eva Beatrice Aste née Leggatt

Miss Deneke recounts how when the wireless announced that Germany had invaded Poland, Mrs Phipps was standing, broom in hand, in the passage at Church Farm. Joan (Phipps) and Mrs Brown, the farmer’s wife, were there. “They stopped to listen”, says Miss Deneke, “and knew they would soon be for it”. The announcement on the radio that war had been declared had a similar effect on Mrs Aste, wife of the vicar, who later said that the announcement had imprinted on her memory every single item of furniture in the room she was in.

Miss Deneke was acutely conscious of the changes the war would bring. She calls the war “a change that divides a past age sharply from an age that is to come”, which may be why she felt the need to record in such detail and with such loving care how Elsfield was affected. She makes the point that the war has scattered the people of Elsfield far and wide. They have met with a wide variety of people and they will be changed by their experiences, so much so that they may find it difficult to resume their former lives.

Rev Aste

She lists who left Elsfield and describes how the village mobilised for war. Frank Sharpe had already joined the RAF when war was declared and unfortunately died of a throat infection in Canada. “Our only loss”. Ben Jones joined up before telling his wife what he intended to do. He and Dennis Lafford were sent to Iceland where Dennis took photographs which showed a bleak landscape opened up, said Dennis, by the Americans who had built beautiful roads. Dennis brought home two beautiful sheepskins of the long-haired Icelandic sheep which are now laid across the foot of the beds in his parents’ cottage. Hubert Webb joined the RASC and was in Greece, Crete, Egypt and Syria, Gerald Colwell was in Canada. Richard Morbey took part in the D day landings and was in Holland. John Buchan Junior was with the Hudson Bay Co. and went to Sicily, Italy and Holland. William was in the RAF, Alastair was in the Canadian Army. “It was with pleasure and surprise that we recognised his photograph published in several newspapers where a young Canadian officer was seen with Gen. Montgomery” writes Miss Deneke.

Rev Aste and Eva Beatrice Aste née Leggatt on honeymoon

Mr Merry and Mr Chaulk were called for home defence and sent to guard the petrol dump at Islip. Betty Webb and Joan Phipps joined the land army. Joan worked at Church Farm but Betty worked outside Elsfield. At the Land Army Rally at Blenheim in 1943 Betty’s shallots won a prize. Dorothy Lafford was stationed with the NAAFI at Kidlington then Abingdon and later at Brize Norton. Rev Aste, Mr Butcher, and Mr Hambidge became ARP (Air Raid Precaution) members. Special constables were Mr Allam, Mr Brown, Mr Lafford senior and Mr Watts. The special constables patrolled in pairs. Miss Deneke knows how hard this extra work was for people whose work for the war effort was the all important one of keeping up food production. “When many alerts came it was hard work for men who had to be up at 5 am for milking”.

Not only the people were affected but the land had to be adapted to the needs of wartime. 590 acres towards the Washbrook and elsewhere were ploughed up and planted with corn and grass to make better grazing for animals. Potatoes were also grown and these were picked by women and children, most of them going to the Army. A War Agricultural Committee was formed, whose Elsfield representative was Mr Watts of Hill Farm, the biggest employer in the village, and this organisation helped with advice and the loan of machinery. During the course of the war men were imported to work on the land. Some Czechs lodged at Forest Farm and later there were Italian POWs, who lifted mangolds and helped with drainage, as well as dredging the river. Vegetable gardens were also important. In 1944, Mrs Phipps won a prize for her garden, and milk from the farms went to Oxford. Late on in the war on her return to England, Lady Tweedsmuir distributed seeds sent from Canada.

There was, of course, a blackout. Everyone had to be careful because a light could be seen for miles – across Otmoor. One night, Mrs Webb heard a great thundering on the door. She was frightened and when she opened it and saw a man in uniform, even more frightened. She thought she might be in trouble because of showing a light, though she had been careful. However the man was a despatch rider and was very grateful that there had been a sliver of light creeping out from the bottom of her door. He had been completely lost in the dark. She gave him a cup of tea which he drank with relish, then set off again. She closed the door behind him and put a mat over the bottom of the door to keep the light in.

School Cottage with the telephone box to the right

In September 1940, during the Battle of Britain, there was an invasion alert. Mr Lafford was called by Mr Watts on the telephone in the kiosk next to the school and told there was danger of an invasion. Mr Lafford ran to the Vicarage to tell the vicar, who along with his wife ran across to the church and began to ring the bells. On that occasion, road blocks were manned at either end of the village all Saturday night and all day Sunday until the danger was past. The observation post was manned and if the Germans had invaded, there were 17 men who had been prepared to die for King and Country. Mr Watts was so thankful that the Battle of Britain was won that he sold a ram and gave the proceeds to the Red Cross.

There was a barrier on the road from Elsfield to Marston before the junction with the Woodeaton road. On one occasion, Miss Deneke was challenged to show her identity card by the person manning the barricade. She was most surprised as, in general, every body knew everybody else. The road barriers were made from ladders mounted on a bicycle wheel at one end and fixed to a post at the other. This made them easy to wheel across and block the road, though how effective they would have been in stopping a tank is debatable.

Sergeant Taylor was in charge of the Home Guard in Elsfield. They had no proper rifles at first but made do with poles and shot guns. They had bunk beds in the reading room at the school and kept watch at either end of the village, two of the men keeping watch at the northern end of the village so they could see over Otmoor and another two at the Oxford end of the village looking towards Headington. They would be on watch for two hours at a stretch. At the end of two hours, one of them would go and wake the next man by banging on his window with a prop. Unfortunately, one time they banged a bit too hard and the window broke. Pinker and Bedding were no. 1 patrol and operated between the observation hut (in the field next to the King Charles Oak) and the north road block. No. 2 patrol was Lt. Corp. Hambidge and Private Boolyer on high ground in the East looking towards Headington. Their job was to look out for enemy aircraft and enemy agents.

There were three sections which made up a platoon: Elsfield, Beckley and Woodeaton. When they did acquire guns, the Browning automatic was manned by Corporal Watts and Privates Pinker and Millington. The Tommy gun was manned by Corporal Maltby. Private Maltby was the dispatch rider and Private Hayes was at the telephone kiosk. He would transmit messages to Private Lafford who would act as runner. The others stayed at their stations where they had a days’ supply of rations, gas masks, eye shades, ointment and field dressings.

Fortunately, there was no invasion but the war did impinge on village life in a dramatic way. Mr Morse found an Anson plane in Woodeaton Wood. It had been there about two days and the pilot was dead. One German plane crashed on Otmoor and all six crew were killed and in 1945, an American Liberator got into difficulties over Headington: the men bailed out and the plane crashed at Forest Farm. When Mrs Merry and Mrs Phipps were cycling near Islip a bomb fell there, missing the petrol dump but destroying a house and killing some pigs. The shock of the blast blew Mrs Merry and Mrs Phipps off their bicycles.

In 1943, Miss Parsons was called upon to provide accommodation for a Canadian Searchlight Company which was stationed in the village for two months. They cooked their meals on Miss Parsons’ oil stove in her dining room. Miss Parsons, determined to do her duty though she was now well on in her eighties, was also prevailed on to help with evacuees.

As Oxfordshire was perceived as a relatively safe place from German bombing, arrangements were made to evacuate children from London. In the early months of the war, Miss Deneke was appointed billeting officer for these children. They were prepared to receive five children. A group of Elsfield residents waited by the old tree (at Tree Cottage) prepared to take them to Mrs Chaulk, Mrs Brown and Mrs Webb, who had all agreed to take a child or two, depending on spare bedrooms.

They waited all afternoon, having been told that the children would arrive in the early afternoon. The bus did not come till six pm, driven by a surly driver. A biggish boy of 14 went to Mrs Webb, two little girls to Mrs Chaulk. Miss Deneke asked where the other three children were. The driver jerked his head in the direction of Church Farm. Miss Deneke hurried in that direction and was confronted by an outraged Mrs Brown guarding the gate. She had agreed to take two school age children but had been left with “a most unprepossessing little mother with one baby in her arms, another clinging to her skirts and in the advanced stages of expecting a third”.

Mrs Brown refused to take them in, which Miss Deneke could understand, given the busy life led by a farmer’s wife. Miss Parsons agreed to take them in on a temporary basis. There was no antenatal clinic in Elsfield and no transport to get the mother to one, so she was eventually found a billet at Horspath and moved there. The mother had cried all the time – her unemployed husband had looked after the children and she didn’t know how. She didn’t understand why the lady had told her to leave London. She went home before long, but Miss Parsons had had a distressing time and her good spare room mattress was spoilt. The whole affair had shocked and outraged her.

Mrs Webb’s boy proved too much for her. He was too old for Elsfield school and was transferred to Horspath where his school was billeted along with his teacher. Mrs Chaulk cleaned the heads of the little girls and got them some extra clothes. She got fond of them and thought she had established a relationship with the parents, but they turned up one day and took the children back to London without even saying thank you.

Elsfield had received the wrong set of children and the reason was that Great Western Railways had muddled up the trains and sent the children destined for Oxfordshire to Bristol and the Bristol train to Oxford. The children they should have had landed in Weston Super Mare.

Food rationing became an all important feature of life in wartime. It was introduce in January 1940 and gave equal shares of eggs, milk, bacon, ham, butter and sugar to everyone. Meat was rationed from March 1940 and in July tea, margerine and cooking fats were added to the list. In 1941, cheese and preserves were added and dried fruit, tinned goods and cerealswere also rationed. Food parcels, often from Canada, provided welcome additional food. Agricultural workers were allowed extra cheese and other foodstuffs at harvest and hay-making time and milk and eggs, being produced in the village, were more easily come by for Elsfield residents than for townsfolk.

The WI was asked to co-operate with the Government. Food Advice Service. Mrs Bartlett, the treasurer, undertook to distribute recipes. Mrs Phipps became secretary of the WI Produce Guild and when a government scheme made 4d meat pies available in the countryside outside rations, she distributed them over a period of four and a half years.

The government gave extra sugar to the WI so they could preserve fruit. This was done in Miss Parsons’ kitchen at Home Farm. In 1940, they made 1,193 and a half jars of jam and bottled 380 jars of fruit. In 1941, they made 399 lbs of jam and 105 bottles of fruit. The jam was collected by the Co-op for sale to their registered customers.

The WI continued tea at its monthly meetings. Lady Tweedsmuir’s impassioned plea not to drop these, because of their social importance, “even if you have to drink cold water and gnaw a carrot” was not ignored. Everyone brought a pinch of their own tea from their ration to make what they called the Elsfield blend. At the first meeting after Lady Tweedsmuir returned from Canada, Mrs Kreyer gave a talk on salvage. Bones could be made into fat, glue and manure, she said. As the war went on, bones became scarcer because dogs were fed on scraps. Bones, ash and swill were kept separately, and all paper was saved for re-manufacture. It was taken to the Manor and collected by Mrs Balfour of Holton Park who collected for the whole district.

The WI arranged to use the school as a rest centre in case of an air raid in Elsfield. That would have been adequate for a stray bomb but they were worried about what would happen if Oxford were attacked and people flooded out of the city into the country, as had happened in Southampton and Portsmouth.

Throughout the war, the women of Elsfield WI knitted for the forces and the Merchant Navy and towards the end of the war “with a feeling of joyous relief” at having pink wool provided for small children in liberated Europe. (Greece and Holland, among other places.)

According to Miss Deneke, the later evacuation was much better planned. In the second wave of evacuations, the 25 cottages were already full so Miss Deneke had to turn again to the farms, which were the only houses with any spare capacity, These however were reserved for soldiers and land workers. Miss Parsons said “with trembling lip” that she would take a “nice mother and baby”. Lady Tweedsmuir had arranged her own evacuees, among them a Mrs Robinson, a London housing expert, who took over some of Miss Deneke’s responsibilities.

Nine further children were brought to Elsfield privately and proper billeting allowances were negotiated by Mrs Robinson. The Vicarage, too, had self-evacuated people who came and went. The children from London were intelligent but unruly. Most were from Holborn and they missed fish and chips, the streets, the shops, and found it difficult to adapt to life in the country so didn’t stay long.

The school garden was involved in digging for victory. The children knitted for the Merchant Navy and collected books for servicemen. They collected waste paper – half a ton – which was stored at the Manor, and horsechestnuts for medicinal purposes which were sent to the national and county collections, and they corresponded with US children after Pearl Harbour in late 1941.

Life at the Manor

After the Tweedsmuirs went to Canada in 1935, the house was empty. During the London blitz in 1940, Lady Tweedsmuir’s mother Mrs Norman Grosvenor came to stay at the Manor. A Red Cross working party met at the manor every week for a short time until Mrs Grosvenor’s health failed, and she died at the Manor later that same year. A further tragedy struck the family when Lord Tweedsmuir himself died in Canada in the same year. He was cremated in Canada and his ashes were returned to Britain and received by Johnnie and William Buchan. His ashes were buried in Elsfield churchyard under a gravestone designed by Herbert Baker and with an inscription which translates as “Here in his own earth, lies a man of letters, who served his country and enjoyed the affection of countless friends.”

The memorial service for him in Elsfield on the 17th February 1940 was held without Lady Tweedsmuir, who was still in Canada. Prof Gilbert Murray, his long time friend and teacher, spoke of John Buchan’s “liberal outlook of this most unusual conservative”. William Buchan read the Death of Valiant for Truth from Pilgrim’s Progress and the Pilgrim hymn was sung. Miss Deneke says that “Four clipped yews stand sentinel over the grave”. These are no longer there, having been removed by the Rev de Vere much later in the century.

Amos Webb, his chauffeur who accompanied him to Canada, died shortly after Lord Tweedsmuir and is buried close by and John Buchan’s good friend Mr WFG Watts of Hill Farm also died before the end of the war, in January 1944.

On her return from Canada, Lady Tweedsmuir entertained overseas soldiers on ‘Balliol leave’. This was a series of courses sponsored by Oxford University. The men came up every Thursday afternoon by bus. Miss Deneke helped Mrs Charlett, the Tweedsmuirs’ cook, Mrs Webb and Mrs Charles Maltby to provide 35 teas each time.

How the soldiers spent their afternoon is not very clear but they were shown a piece of embroidered silk from Japan, an edition of a book about Italian monuments given by Mussolini to John Buchan, and a signed photograph of the King, Queen and Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret Rose. How entertaining they found this is not recorded but on their way in and out they were surrounded by village children who hung about waiting for the soldiers to give them chewing gum.

Alistair Buchan’s wedding to Hope Gilmore

Two years after Lord Tweedsmuir’s death, there was a much happier event. Alistair married Hope Gilmour of Ottawa on 11 April 1942. Dr Ernest Walker composed a new setting of ‘I will lift up mine eyes to the hills’. Margaret Deneke played the piano, specially imported for the occasion. Mr Rushworth brought the choir boys from St Michael’s Church, Oxford and Alistair was married in the uniform of the 14th Canadian Guards by Canon Hepburn, Chaplain to the Canadian Forces, and by the Reverend Aste.

Alison Aste’s wedding to Kenneth Grayston, 1942

The church was packed, even the chancel being full. Alistair and Hope were pelted with primroses by the children, confetti not being available because of wartime restrictions and the wedding reception was at the Manor. Lady Tweedsmuir had to borrow crockery and glasses for the occasion. Also married in 1942 was Alison Aste, one of the two daughters of Rev Aste.

Rev Aste at Water Eaton after christening

Towards the end of the war, there was a great flight of planes, crossed Elsfield flying in close formation on their way to France presaging the end of the war and to celebrate VE Day, the village was gay with flags. There was tea at the Manor and games and sports. On VJ Day, there was a children’s party at the school organised by Mrs Merry and Mrs Winfield when every children was given half a crown.

It was indeed the end of an era, and as if to underline that fact, in March 1945, that pillar of village life, Miss Parsons, died at the age of eighty-nine.