1953: The Sale of the Manor

Harry Adams, gardener to the Buchan family

Without John Buchan at the helm, both the Buchan family and the village seem to have lost a sense of direction. Without his presence and earning capacity, the house began to crumble and was impossible for the family to maintain. They struggled on until 1953 when the house was put on the market. It was not, of course, merely the house. There was the accompanying land and the cottages which were occupied by the widow and disabled daughter of Mr Paintin, who had worked for Mr Watts at Hill Farm, there was Amos Webb’s widow, who by 1953 was in hospital. There was Jack Allam, the gamekeeper and Harry Adams the head gardener, none of them in the first flush of youth. The Paintins and Mrs Webb were in cottages which had been tied to work at the Manor but had not paid rent even after their menfolk had died. Disentangling from all these dependents would not be easy for the Buchans.

The Paintins were issued with a notice to quit their cottage which prompted James Paintin to write to the Buchans on his mother’s and sister’s behalf. They lived in one half of what is now Rose Cottage, while Mrs Webb lived in the house next door.

Dated 29th October 1953, James Paintin’s letter runs as follows:

“Dear Lord Tweedsmuir, It was indeed a shock to my mother and Ruth when they received your notice to quit the cottage at Elsfield in three months. The blow was all the more severe as Mr William Buchan had told mother the cottage would not be sold and she had nothing to worry about.

They have nowhere to go and there is no cottage in Elsfield or anywhere else. My mother would have paid rent after my father died if she had been asked and is prepared to do so now. She did ask Lady Tweedsmuir some time ago how she stood in regard to the cottage but nothing else was mentioned.

My mother is now 77 years of age and Ruth being crippled it is a great worry to us all after they have lived in Elsfield for 40 years.”

In December a letter from Mrs Lane’s solicitors indicates that the Buchans were as upset as the villagers whose fate they could no longer control. A letter from Messrs Loft and Warner of St Giles, Oxford, acting for Mrs Lane, says in the most restrained manner possible:

“There is one phrase (in your letter) which I find hard to follow. In the matter of the cottage occupied by the Webbs and Paintins, you say that Mrs Lane should have little difficulty in taking action for eviction, if she is really hardhearted. I think this is a little hard on both Mrs Lane and myself, as she has nowhere to keep her servants if she buys the Manor, and the circumstances being what they are, I have had no option but to serve these notices on these folk, deeply as I regret doing so.”

The Paintins did not give in easily, however. Lady Tweedsmuir’s companion, Miss Taylor, writing from Linton Lodge Hotel on 21st January 1954 encloses a note to a Miss Winch, presumably a legal secretary, about the conditions under which Mrs Webb and Mrs Paintin were allowed to live in the two cottages. By this time the Manor had been sold and Lady Tweedsmuir had taken temporary refuge at the Linton Lodge hotel before moving to the Cotswolds.

Mrs Webb, says Miss Taylor, is unlikely to come out of hospital. Neither Christ Church, Mr Watts, who employed Mr Paintin, nor Lord Tweedsmuir have any responsibility for the Paintins, and in addition Ruth is crippled and unable to work. Mrs Paintin has, however, a son in Oxford and a daughter in Aynho, whose responsibility they are. In a Machiavellian touch, she advises Mrs Lane not to try to solve the problem herself but to deal with it entirely through her solicitors, since the three months notice has now expired but the Paintins are still in residence. She writes:

I imagine she (Mrs Lane) proposes having work done in the two cottages and by the time she does move into the Manor any odium for the eviction of the two families will have died down. If she leaves it and tries to deal with the matter herself she may find herself unpopular.

The Paintins stuck it out, however, and did not move away. They lived there until Ruth married and Mrs Paintin died. Mrs Lane, being a kind and generous woman, appears to have ignored Miss Taylor’s advice, and had the stable block adapted so her maids could sleep there.

There were similar insecurities about employment. There are several letters from Alfred and Frances Sumner at Beckley. Alf was working as a woodsman for the Tweedsmuirs, looking after Noke Wood, and Lord Tweedsmuir (the second Lord Tweedsmuir, eldest son of John Buchan) more or less gives Alf carte blanche to shoot in the wood and cut any timber he needs. Alf angles for more work from Lord Tweedsmuir, as he has only £2 a week from the Army, but his lordship replies that he is sorry he cannot afford to employ him more than he already is doing. The final letter, when Alf is 79 and Frances 78, says that they now attend the Over 60s Club in Beckley and are the oldest people to do so. Their grandson has learnt to drive and is doing his A levels. They are very proud of him and love him very much. The Sumners seem to have held no sort of grudge against the Tweedsmuirs, and in fact probably did quite well from the association, given that Alf had the free run of Noke Wood.

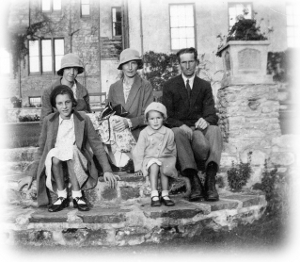

Harry Adam and family in the Manor grounds

This was not the case with Harry Adams, the head gardener, however. In a letter dated 20th September 1953, Harry Adams tries to find out what his position will be when the new owner takes possession. He has been told that the new owner will probably bring her own gardener and wonders if that means he will have to be an under-gardener. That, he says, will not suit him at all and he asks for a clear explanation of the position, pointing out that after all these years as head gardener he cannot work for someone else. He will have to look for another position. Lord Tweedsmuir says he will press the new owner in the strongest possible terms to employ him and says his job is secure until the Manor actually passes into the hands of the new owner.

In The Rags of Time, William Buchan describes a conversation he had with Harry Adams. “I had to make a round of farewells, explaining once again how necessity had forced us to sell the property, and how I was sure that the new owner would wish to keep on good and experienced staff. Adams shook my hand, his face expressionless, and then turned his back on me and looked out over Pond Close towards his fruit garden. Feeling miserable enough, I felt also a kind of guilt. That thin, stiff back seemed to say, quite plainly, ‘You couldn’t hold on, could you? And what’s to become of me?’ He said no word. A few months later, turning into the heavy traffic on the Oxford by-pass, a mile away, his bicycle was struck by a car and he was killed instantly”.

William Buchan is actually misremembering here since Harry was very much alive in 1956 when he writes to thank Lord Tweedsmuir for his Christmas present. It was perhaps guilt that made William attribute in some part Harry Adams’ death to the way he had been treated, not so much by the Buchans as by the system. Presents from the Tweedsmuirs continued to pass from them to the various people they had once employed and letters of thanks continued to be posted from Elsfield to the Tweedsmuirs, but it was the end of an era, a sad winding up of affairs.

In 1957, Isabel Allam, widow of Jack Allam, writes to the Tweedsmuirs to thank them for their kind letter of condolence. “I know you will miss him very much like I do”, she says. “We had a very happy life together, but I am glad he is at rest as he had suffered long enough”. She goes on to add, “You all speak so highly of Jack, which is a great comfort, and Mr Alastair put such a nice piece in the Oxford Mail about Jack”. She ends “With many thanks for all your kindness”, and that seems to have been how Elsfield people viewed the Tweedsmuirs.

The obituary written by Alastair Buchan is indeed a moving tribute to a man who played such an important part in his young life. It was included by Helena Deneke as an addendum to her account of Elsfield village life during the Second World War.

Jack Allam’s Obituary by Alastair Buchan

Last week, one of Oxfordshire’s great countrymen died and was laid to rest in the churchyard at Elsfield where he had spent most of his life.

Jack Allam was keeper to my father and brother during the twenty-five years that my family lived in Elsfield. He was born in the mid-seventies (1870s) in a house on the road between Stanton St John and Islip that had once been an inn and a haunt of highwaymen, close by the tree where Haynes, the boldest of their number, was hanged.

His whole life was spent within the compass of a few miles, though he once went to London on foot in the early part of the century, and once again to see my brother get married and tasted salmon mayonnaise with the deepest disapproval.

The word gamekeeper suggests trim woodlands and battues of pheasants, but Jack’s real duties were less to keep an eye on our few and well-poached spinneys as on the country rearing of a hatch of small Buchans.

It was he who taught us how to flush out an owl from a nest in a hollow tree not by beating but by rubbing a stick along the bark, how to destroy elusive jays and magpies by luring them into shotgun range by imitating the scream of a rabbit in the grip of a weasel, which aroused their predatory inquisitiveness; how to wait motionless for mallard on Otmoor and above all how to look for birds’ nests.

It was he who discovered a jackdaw’s nest lined with scraps of the original manuscript of my father’s History of the Great War which he had imprudently discarded the previous autumn and the daw had prudently salvaged.

Though his theory of shooting – a foot and a half in front of a pigeon, three feet in front of a mallard- was directly contradictory to that taught by the experts, he very rarely lifted the antique hammer gun which he carried in preference to any other except to bring down his quarry.

Jack had no children of his own, and the loss of a beloved stepson lost in the war was the greatest sorrow of his life, but he was endlessly kind to them. He tended the savage and ungrateful goshawks and peregrines with which my eldest brother’s passion for falconry filled the outbuildings at Elsfield.

When I formed a ‘pack’ of beagles consisting of two Christ Church puppies at walk (unbeknownst, fortunately, to the Master, Charles Clarke Brown, of Kingston Blount) a spaniel, Jack’s own rangy nondescript, he enthusiastically whipped in, knowing more about the habits of our local hares than any professional huntsman. His kindly gnarled face was a beacon to at least three generations of children.

The real Oxfordshire accent – a burry lilt with an ‘ah’ at the beginning of each phrase – fortunately shows no signs of retreating before BBC English, and in Jack Allam’s bass voice it was so thick sometimes that it was hard to understand.

He used words that went straight back across the centuries; the Saxon word ‘ger’ for carrion crow, ‘puggling’ for poking a squirrel’s nest or down a rabbit hole.

Though he barely had the benefit of Foster’s Education Act (of 1870) he maintained that he ‘could read reading but couldn’t read writing’ meaning the printed word but not handwriting. He stoutly maintained he could write but avoided putting it to the test. Having a memory unblurred by too much printed information, he could tell us the exact course of a famous run by the South Oxfordshires (the hunt) in the nineties, just why some long forgotten Victorian squire was sold up for debt, and stories of highwaymen, gipsies and rick-burnings that were part of an inherited race memory stretching back to the eighteenth century and further.

Though he lived well into the era of the Cold War, he was unshakeable in his inherited belief that if any danger threatened England, the French were at the bottom of it. On embarcation leave for Normandy in 1944, his parting shot to me was to ‘have a go at they Frenchies’.

A relic of an older, much poorer Oxfordshire countryside was his partiality for strange dishes, red squirrel, or hedgehog baked in clay, eels and pike. He was an ardent fisherman extracting large chub on summer mornings with a live bumble bee expertly dapped along the surface of the Cherwell on a long pole.

My father drew on Jack Allam’s character and experience in the only children’s book he wrote, The Magic Walking Stick, and it is pleasant to think that two such close friends now lie beside each other in that quiet place.

Alastair Buchan, 13th April, 1957.

The Buchans were not the only children in the village who benefitted from Jack Allam’s involvement. Arthur Phipps, now in his eighties, still treasures the catapult made for him by Jack when he was a small boy.