Elsfield farmers

Following Mr Watts at Hill Farm was his son-in-law Frank Hays, followed by James Garson and his family who came to Elsfield in 1965. James not only ran the farm in Elsfield but was also a consultant for several estates up and down the country, stretching as far as Scotland, where he loved to go fishing. His wife Faith describes how his work developed:

“He went out and helped others who had huge estates advised by either solicitors or accountants and they were in a muddle. Sometimes the husband had died and the land had been left to the son or a wife who was being diddled by a farm manager or in trouble and James would then take it over and sort it out. He’d visit it either once a week or once a fortnight. He had four young women helping with the office side of things and three men, one of them an agronomist, who all had different jobs.

That was where lovely Jane fitted in. She did all the original book-keeping in long hand. Elizabeth Lees deserves the credit for all the original hard work, helping James, who just accumulated workand accumulated. He just went on working hard. It got too much for one man and he retired in 2000.”

Keith Bradford

Retiring at the same time as James Garson was his foreman in Elsfield, Keith Bradford. Sue and Keith Bradford arrived in Elsfield on 3rd June 1965, their wedding day. They set up home at 2 Christ Church Cottages where their three children were born. Keith was a tractor driver before being promoted and Sue had been a nanny.

In 1965, Mr Willis lived at Forest Farm and farmed there. He had mostly dairy cattle. When Mr Willis retired the land was split between James Garson and David Brown, son of Jack Brown. The Bradfords went to live in Forest Farm when Keith was made foreman.

The crops grown were wheat, barley, oats and oil seed rape. This latter crop was considered by many people to be a grain new to England in the 1970s. It had, however, been grown in this country since the 16th century. It was grown extensively in the east of England, in Lincolnshire in particular where it was highly valued because of the oil it yielded. It went out of fashion in the early 19th century because of the import of cheap oil.

Christ Church’s Longhorn cattle

The Browns had pigs and sheep while James Garson had a herd of suckling cows at one time and the Christchurch Longhorns were brought up to Forest Farm to winter. In summer, they were sent back to Christchurch Meadows in lorries.

There were also pet animals. When Sue and her family moved along the road from Christ Church Cottages to Forest Farm she walked there with her pet lamb and ewe. She also had two pet geese. Sue had various jobs in her capacity as wife of the farm foreman. She would feed the students who were generally lodged in empty cottages in the village. They would come in the summer to help with farm work from Reading University and Harper Adams College.

At the end of harvest she would spend a considerable amount of time on the phone organising the lorries to fetch the grain (mostly barley and wheat). James Garson also had land at Finmere, the other side of Bicester. Keith would sometimes have to take the combine up there, in which case she would have to bring him back by car.

James Garson planted a lime tree outside Forest Farm which Sue watered every day till it became established. It is now fully grown.

Cattle farming

Having a herd of cows even if they were grown for beef and therefore did not need milking, was very time consuming. Heifers are not ready for breeding till 14-18 months old and the gestation period for a calf is 40 weeks. About seven months after the calf is born it is weaned and for the next 6-10 months it will forage and graze.

They cannot however just be left to get on with their lives. They have to be watched carefully for the onset of disease. The cows in Lowsey Mead were prone to disease, two in particular: Fog Fever and New Forest Eye. Fog Fever is a disease of autumn when cattle are moved from dry summer pasture to a lush autumn one. It causes acute pneumonia, which gives severe breathing difficulties and results in the affected animal often separating itself from the herd. New Forest Eye, unlike Fog Fever, affects young cattle and is a bacterial infection causing conjunctivitis and eventually corneal ulcers. Another disease which happened occasionally was Lown, a bacterial infection between the two halves of the hoof which the vet had to treat with penicillin.

Friesian Charolais calves

At Forest Farm, they kept Friesians, the black and white cows which are a common sight in the English countryside. The heifers were always put to a Hereford bull for their first mating, because Hereford bulls are smaller than Charolais. On their second mating they could be put to the Charolais bull. Charolais cattle, a French breed, were introduced into Britain because their meat, having been bred for pulling ploughs rather than for eating, is very lean, which is what the eating public wanted. Charolais cattle have large heads and cows sometimes had difficulty delivering the calves, which were also difficult to get going. They would be born alive but sometimes, as Sue put it, they didn’t seem to have the will to live. The Bradfords had to blow up their noses and occasionally the vet would throw a calf over a gate to stimulate it to breathe. The two Charolais bulls were called Algernon and Loomy.

The cows were fed on hay in winter, and were kept inside and even in April were still being fed hay. They were moved out into the fields as soon as the new grass was showing and had to be moved from field to field as they ate the grass.

Friesian heifers

Barns were cleaned out after the winter use by the cows and in Spring the new heifers were drenched. Drenching is a process by which chemicals are given to cattle for a variety of diseases such as lungworm, warble fly or deficiencies. Warble fly burrows through the cow’s body and emerges at the top, thus making a hole in the skin and spoiling the hide. Drenching can be done by squirting the stuff into the mouth of each cow as it is held in a cage, as at a rodeo, or the cows can be given it by hypodermic needle under the skin. The cattle were drenched again in November for warble fly and tested for brucellosis and TB. Keith once accidentally stuck himself rather than the cow with the hypodermic needle. Fortunately it did him no harm.

The cows had to be fed CIO which is a balanced food supplement high in magnesium. The soil here is deficient in magnesium which causes Staggers in cows. It can be administered either into the main artery by hypodermic needle, in tablets for them to lick out in the fields or by spreading Epsom salts on the field. The advantage of giving an injection is that you know how much the cow has had. Each cow was given 2 oz of magnesium ocode or calcined magnasite a day.

Other jobs which took up much time and energy were de-horning the young cattle, maintaining a good water supply for them, cleaning out the calf box ready for the birth of calves in July, fixing ear tags on them and branding them, and cutting hay for winter feed.

A story which illustrates the sometimes extreme conditions people had to work in was one told by Keith.

One very cold night, Keith went out to look at the cattle and felt there was something wrong, because the cows were distressed. In the field there was a sewer trap which had been fenced round but Keith found that the cows had pushed down the fence. One of the calves was swimming in the hole full of water where the sewage had been. When James Garson was called he said they would have to shoot it, but Keith said no, he’d ring the Fire Brigade, which he did.

It was so cold that night that diesel was freezing in the engines of the tractors. The Fire Brigade turned out and said they could use one of their hoses flat under the calf and pull it out that way. The question arose as to who would put the hose under the calf. It would entail jumping into the freezing sewage pit. Keith said he would do it but James Garson said he would and he did.

When the calf was pulled out none of the cows would have anything to do with it but Keith took it into the shed and cleaned it up. Meanwhile James went home and used all the hot water in trying to get clean. His wife, Faith, couldn’t have a bath the following morning because there was no hot water. Sue brewed copious amounts of tea and poured plenty of whisky in it for the firemen, to warm them up. Keith was full of admiration for James Garson’s behaviour that night.

The beef herd was sold in 1981 soon after the Pick Your Own started.

Arable farming

Student with John Deere combine harvester

James Garson implemented many changes in the landscape. Because of the large equipment they were using it was very difficult to plough small fields, so many of the hedges and fences had to be removed. There were two barns made of worked stone, one at the top of Jubilee Wood and the other in Lower Swarth, but these were no longer in use and Christ Church had them pulled down. There were also two cottages rather than one at Field Barn Cottage, now occupied by Mr and Mrs Maltby.

After the implementation of the Set Aside[1] scheme by the European Union in 1988, James Garson had a conservation plan drawn up for the land he managed in Elsfield. Keith had to leave a three metre wide strip around each field, which was time-consuming and quite difficult to do. It was decided that the money provided under Set Aside would not be enough to be worth implementing the scheme recommended by the Farming and Wildlife Group in Berkshire and Oxfordshire.

Growing crops

Keith’s farming diaries have provided a wealth of information on which the following charts are based.

The Farm Year

“The weather controls you”

| February: | Plough and sow spring barley. Fertilise. Spray for weeds. |

| May: | Make silage. |

| June/July: | Make hay. The hay was grown in small paddocks. Hay was also bought in for the cattle. |

| July: | Harvest. Sow winter barley and Oil Seed Rape (OSR). All seed bought in for sowing later. |

| August: | Winter wheat harvested, sometimes through to September, depending on weather. |

| August 20th | OSR put in along with compound fertiliser P and K. |

| Sept/Oct. | Winter barley sown followed by winter wheat. Linseed was grown in 1999. It was put in at this time of year. (There was a five year cycle: barley, OSR, wheat, wheat, wheat. OSR kills off wireworm)) |

| November: | Winter ploughing for spring sowing. |

| December: | Checking fences. Loading corn to go out. |

Farming practices

In the 1970s, it was common practice to burn the straw after harvest. This cleans up the soil and makes it easier to cultivate. The order of work then when growing crops was:

- Superflow to a depth of 6-8 inches. In gardening terms this is digging.

- Use the spring tine cultivator – this levels the clods by vibration.

- Roll to level the surface.

- Drill: sowing the seeds. To do this you use a

- Disc – this cuts through the soil

- The Suffolk. This leaves a channel one and a half inches deep for wheat, barley and oats.

- Roll with a Cambridge roll.

Having sown the seed the following work has to be done:

- Spray weed-killer pre-emergent (rarely) or post-emergent, depending on the weed. Fertilise. This was sometimes put in with the seed.

- Wait for the crop to grow!

- Sometimes spray for beetle in the corn head. You had to be up by 4 am to detect this as any later and the beetle would have flown.

- Harvest: 12-14% moisture was expected in the grain. If it got up to 20% a drier was used. This was to stop the grain from rotting. The underfloor drier in the barn had fans either side. The drying was controlled. It could not be done on a wet day as this would bring moisture in, though it could be done if it was frosty. There was a humidity detector on the fan.

The grain was kept till the price was right. It was tested every week but the smell revealed the moisture content. The grain could be kept for up to a year, but it was not usual to keep it so long.

Crops grown were barley, wheat for milling and animal feed, oil seed rape (OSR), kale (for cattle feed), grass, and in 1999 linseed.

Maintenance work

There is a great deal of maintenance work to be done on the farm. Some farms have their own workshop.

| Maintenance of machinery (Some of this was done by the farm workers, some by contractors): | ploughs, tractors, sprayer, discer, rotavator, springtiner, augurs (These were machines like giant tubes containing a screw which moved the grain into the silo from the harvester) |

| Maintenance of land: | ditches kept clear; hedges lopped; bushes burnt; wet land moled (i.e. land drains were put in); acid soil limed; footpaths maintained; drives laid |

| Maintenance of buildings and households: | plumbing; cars; painting; cleaning out sheds. Control of pests: rat traps baited; moles killed; slugs pelleted (if you put a hollow container upended in a field and counted the number of slugs you could decide whether or not you needed to use slug pellets); rabbits shot. |

Chemicals used on the land in the last quarter of the 20th century

Fertilisers:

- Nitram is a nitrogen based fertiliser which increases the yield. It is used as a top dressing.

- Fertiliquid. Supplied by Fisons. This was a general fertiliser.

Weedkillers:

- TCA. Suffix. Bostok. This was a weedkiller in a spray granular form.

- Donex is a weedkiller. It was used on grass in the Hillingdons which was the worst field for weeds. It is a selective weedkiller and will get rid of poppies, vetch, corn marigolds.

- Dicurane, a weedkiller for pre-emergent crops.

- Granoxon. This was a weedkiller but it did not kill the roots of weeds. It was useful at harvest time, however, because it desiccated the weeds. It was a carcinogen which caused throat cancer. Keith always used a mask. It was not so good as Roundup, which had not been invented in the 1970s. It was used on couch grass in wheat in Sandfield.

- Avenge. This became available by 1981 and was used to get rid of wild oats. Previous weedkillers for wild oats had been so expensive that it was cheaper, if there was not too much wild oats, for Keith to get about a dozen women from Marston to go “roguing” i.e. pulling the wild oats out by hand. He did this by contacting his sister who would ask around to see who wanted some seasonal work. Wild oats are easy to spot because they grow taller than cultivated oats. They were pulled out when they were about 4-5 inches tall. The price for oats went right down if the wild variety was present.

- Chormaquat was a growth inhibitor to prevent OSR from growing too tall.

- Tilt. A fungicide sprayed on.

- Kerb. A weedkiller to take out the previous crop from OSR.

[1] This was a scheme brought in by the European Union with two aims: to reduce food surpluses such as the butter mountain, and to deliver environmental benefits.

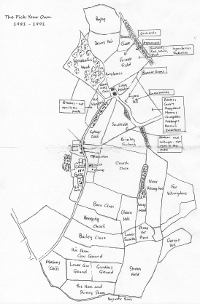

The Pick Your Own

Pick Your Own plan

In 1980, James Garson decided he would start a Pick Your Own, where people could come and pick their own soft fruit. This started on Lyme Hill.

PYO runner beans

It was so successful that it soon expanded. Lyme Hill became the site of strawberries and asparagus. (The sprew, the thin, late asparagus, is very good chopped up in salads. It tastes like fresh peas.) An orchard was planted in Forest Field because it was damper there and here they grew Golden Delicious apples, Cox’s, Bramleys, and Grenadiers. The plum varieties were Early Rivers, Marjorie Seedlings, Victorias, and damsons. Vegetables were grown in Sandfield and in two poly tunnels in Woodcock’s Close they grew cucumbers and peppers. The Hangers were given over to potatoes while Forest Farm had asparagus, cane and bush fruit.

They supplied Le Manoir au Quatr’ Saisons, Raymond Blanc’s famous restaurant, with early potatoes but not main crop and vegetables.

Barn at Forest Farm being altered for a PYO shop and cafe

Christmas trees

The main shop was in the barn at Forest Farm (what is now the Montessori school). Judy Johnson and Sue Bradford ran it between them. They had a tea shop in the balcony and eventually were selling so much they had to buy in extra. So as well as all kinds of fruit and vegetables, they also had cakes, apple pies, and Cottage Delight preserves.

PYO till

A number of fir trees were planted by the reservoir behind Church Close for sale as Christmas trees. Some are still there grown rather too big for bringing indoors.

PYO stall

The PYO continued for about 15 years and was closed because the person employed by James Garson to run it proved considerably less competent and dedicated than the Bradfords. However, all was not lost. The EU provided a grant to grub up many of the trees and burn them!

Farming in the 21st Century

The Brown family, who in 2009 are the only farmers left in the parish, are descended from two farming families who came to Elsfield in the early years of the 20th century. Gilbert John Brown was appointed Clerk of Works to Christ Church when the Parish was sold to the College by the Parsons family in 1919. The Brown family now farming in Elsfield are descended from Gilbert, whose son Jack married Dora, one of the seven daughters of the Watts family, who came to live at Forest Farm at roughly the same time as the Browns. At the time the Watts family moved to Elsfield there was no ring road and the family had to drive their goods and animals through the centre of Oxford, through St Clements and along the Marston road to get to Elsfield from the west of the county.

Since the year 2000 all the land in and around the village of Elsfield has been farmed by the Brown family: David Brown and two of his three sons, Martin and Richard. David and Martin Brown live at Sescut Farm, which is on low lying land near the River Cherwell, while Richard lives in Elsfield village at Church Farm, where his grandfather Jack once lived and farmed. Where once Church Farm employed 14 men, the Browns now use machinery and employ only students and family members at busy times of the year.

Pigs

Jamie with the pigs at Sescut Farm, 1989

There were pigs at Church Farm until 1995 and at Sescut until 2008. The late 1990s were bad years for pigs, and in 2001 came the terrible scourge of foot and mouth disease. In the 90s, £15 a pig was being lost on every animal sold, and the Browns were selling 300 pigs a week. Until 2001, there were 500 indoor breeding sows and 200 outdoor pigs. They were producing 1500 pigs a year which were sold through two outlets: Banbury market, one of the most important markets in Europe, and Thames Valley Pigs, an organisation which marketed 35,000 pigs a week. The pigs were reared till at 17 weeks they reached 95 kilos, when they were sold for bacon.

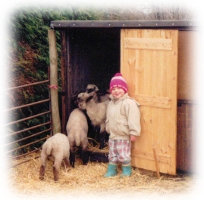

Sheep

Jamie with the lambs at Last Cottage, 1990

Until 1990, there were 1500 breeding ewes at Sescut producing lambs which were reared till they were half grown (a half grown lamb is called a store lamb). They were grazed on a one year ley system. This means that the grass was planted for one year then ploughed up. This gave fresh pasture for the sheep, which was beneficial because there were no parasites in the ground to infect the animals, and it provided a break in cereal production, which meant a clean start for the wheat.

The ewes were sold in 1990 and Richard Brown bought store lambs to fatten over winter on other people’s land. Stubble turnips were also grown on 60 acres of James Garson’s Home Farm land. These were planted after July when the arable crop had been harvested, and were left in the field for the sheep to graze on during the winter. There were up to 4,500 lambs, North Country mules: Swaledales crossed with bare-faced Leicesters, which give a high milk yield and are very fertile, producing two plus lambs each. These were crossed with a Suffolk or Charolais ram, giving a good amount of meat. The wool was worthless. It cost £1.50 to shear a sheep and the wool was worth only 50p. Shearers from New Zealand and Australia would come over, and one year a “golden shearer” from New Zealand came over, who could shear 150 sheep in a day. The wool was sent to Bradford.

For the last five years at Sescut there have been 300 ewes lambing early. They are reared for a year, bought at 6 months old in September and sold the following August to breed. This is done because it is the least amount of work. They are bought largely at Hawes, in North Yorkshire. There is a big four-day sale there where 50,000 lambs are sold every day.

When Kim and Richard lived at Last Cottage Kim had two jobs: she recorded milk – milk has to be sampled on a regular basis and checked for disease – and from January to March would go out contract lambing. Kim and Richard now have a small flock of pet sheep. They lamb them every year and have kept the ewes. Male lambs are castrated as soon as they are born, but one of the markets for them is the Muslim community, who regularly kill and eat lamb at the festival of Eid. Muslims like their lambs whole, not castrated, so this is a problem for sheep farmers.

Sheep usually live for about eight years. They are born with 8 milk teeth, two of which fall out the first year and are replaced with two stronger teeth. Sheep of this age are called “two-tooth”. The second year two more fall out and are known as “four-tooth”; the third year “six-tooth”; by the fourth year they have a full set of eight teeth. (This is on the bottom jaw. They have a hard palate on the top jaw.) By six years they start to lose teeth and by 8 years are broken mouthed, which means they lose weight, the end of their useful life.

Shooting

James Garson was very keen on shooting. Although the Browns were responsible for the woods, they allowed James to shoot there. He kept a fulltime gamekeeper and in the early 1980s the Browns shared the keeper with him. James used to buy day old pheasant chicks and rear them and the partridges would be on Brown land.

Nowadays, it is a small family shoot. The Browns invite their friends over and it is a reciprocal arrangement. It is a communal tradition in this neighbourhood. They shoot mainly pheasants which go to a game dealer and are sold at farmers’ markets. The dogs they use are spaniels and as they no longer have a gamekeeper they buy in poults, eight week old half grown chicks which are put into pens. When they are fully grown they are released into the wild, but there are hoppers around the fields with feed for them. Wet weather can kill large numbers of them.

Harvesting

Towards the end of a cold August in 2008, the Brown family were harvesting wheat in Church Close, the field behind the grain stores at Home Farm. As well as wheat, they also grow oil seed rape, oats and tick beans for winter feed for animals.

In the field were William, aged 16, Sarah, aged 19, both of whom were driving tractors pulling trailer-loads of the harvested grain. When the trailer was full the grain was taken down to the shed to be stored. Harry aged 17 was taking the baled straw down to Sescut while George aged 20 was on the bale cart. John Henry, aged 14, had been there earlier taking photographs of the process. Richard was combining. A contract baler is brought in to bale the straw because they don’t use much, the farm being now almost entirely arable. Some straw is chopped and ploughed in while the rest is baled. About 1000 half ton bales are kept to make walls in the barns but the rest are sold to farmers who have livestock.

Combine-harvester

The tractor pulls a trailer alongside the combine-harvester, which spews the grain into the trailer. They aim to fill the back of the trailer first so they can see how full it is. With wheat they have a full trailer every 15 to 20 minutes but OSR is slower, taking 30-45 minutes because of the smaller yield.

The combine-harvester is French-made. (There is not much agricultural machinery made in England.) It is controlled by computer and is a fearsome machine. It has a tank which holds eight tonnes of grain before it needs to be transferred to the trailer. It drives itself, cutting a swathe 30 ft wide, with a camera sensing the edge of the wheat to be cut. The computer registers the area covered (in this instance 11 hectares), the crop yield, (average 12.5 tonnes per hectare), the moisture level (16.9%) and the tonnage (140 tons). This is all recorded on the computer memory stick in the machine as the grain is being harvested and the information is then transferred to the main computer in the office. The yield is colour coded on the print out, giving the number of tonnes per hectare, so it is easy to see which field or part of a field is producing most. The amount of fertiliser needed for the following year is then calculated.

The wheat being harvested was winter wheat of the variety Solstice, which was sown in autumn 2007. There is also spring wheat which is sown in February and harvested in September. Winter wheat is grown in Elsfield because in parts the soil is very wet and Spring wheat would not have sufficient time to germinate and grow well. Winter wheat is the highest yielding cereal crop in the UK and has the most acreage. Yields are typically eight to ten tonnes per hectare, so the field being harvested was a good one. The corn is short because in Spring a growth inhibitor is applied which stiffens and shortens the wheat, and this is also used on the OSR. (Straw for thatching is longer and is now specially grown for the purpose.)

The wheat varieties are graded 1, 2, 3 and 4, with 1 and 2 being suitable for milling and 3 and 4 for animal feed. The Browns grow four kinds of wheat: Solstice, Cordiale, Einstein and Humber. The first two are milling wheats which they harvest first because it is more valuable and the other two are for animal feed. Generally, the wheat for animal feed gives a higher yield than milling wheat but is poorer in quality, that is, it has a lower protein content.

The price for high quality wheat is ultimately determined by commercial bread and biscuit manufacturers. There are two main quality characteristics which are important to them which affect the way flour behaves when it is cooked. One is the amount of gluten in the wheat and the other is the activity level of an enzyme called alpha-amylase. For bread, strong extensible gluten is needed so the dough will rise without leaving holes in the baked bread. For biscuits a weak gluten is required. The enzyme alpha-amylase turns starch to sugar, which prevents proper dough characteristics developing, so it is important to have a low level of the enzyme in the wheat. This is measured by something called the Hagberg falling number (HFN). A high HFN means the flour is less degraded.

The moisture content is important. It has ideally to be 15%. This is monitored by the combine continuously and was over 16% when they started harvesting in the morning but had dropped to 15+% by midday.

The soil is tested during the year by agronomists who advise on how much and what kind of chemicals to apply. Fertiliser is very expensive, so it must be applied carefully. Sarah, who is studying agriculture at Newcastle University, tested each field for potassium and phosphorus a few months ago. Too much potassium inhibits the magnesium uptake by the crop.

The harvested crop is sold to corn merchants at Thame and Daventry. Wheat is fetching about £115 a tonne at the moment, with OSR fetching about £280. OSR is taken for crushing at Erith, on the Thames estuary, or Liverpool. The Browns themselves transport the grain on behalf of the corn merchants. They also take corn to Rank/Hovis in Southampton for export, wheat to Corby for the flour mills and beans are taken to Tilbury, again for export, or Enstone for local feed mills.

Black grass, an annual weed the seeds of which can contaminate a crop, has been a problem at Sescut this year because of the wet weather. It is hard to control and they have to plough the soil to get rid of it. In the past straw and stubble burning destroyed a significant proportion of the seeds but this is no longer an option. In lighter soil a cultivator is used immediately after harvesting over the chopped straw. The cultivator turns the surface over, a process which produces a false seed bed where the weeds germinate. The weeds are then weed-killed with a non-selective weed-killer, typically Roundup, and the soil is drilled and rolled. A pre-emergent selective weedkiller is then used which stays in the soil. This allows the wheat to grow.

Spraying of crops is carefully controlled. There must be a six metre buffer zone between crop and watercourse and low drift nozzles are used at all times. OSR is sprayed with Roundup before harvesting to dry it and make it easier to harvest and whereas in the 1990s OSR was used as a break crop so three or four crops of wheat could be grown on the same land in consecutive years, wheat and OSR are now grown in alternate years.

There is no shortage of wildlife. There were eight fallow deer in the field before they started harvesting and there were bare patches in the crop, caused by badgers. There are pheasants in the corn and buzzards and kites, which eat mice and voles, were hovering overhead when they started cutting the wheat. Sarah’s sharp eyes spotted a hare and a couple of hobbies swooped down for food while we were in the field.

Now, in 2009, the land is almost entirely given over to arable crops: wheat for milling and animal feed, beans for animal feed, and Oil Seed Rape.

Based in the barns belonging to Home Farm is a riding stable which uses a large part of Sandfield for grazing the horses in winter. In summer, when the land has dried out, they move further down the hill.