View the Oxford Times article on the Parsons Family >>

June 2011 issue, pp. 31-35 (free registration)

The Parson’s Family:

- Herbert Parsons (1822-1911)

- Louisa Parsons née Thomson (1825-1892)

- Mary Jane Parsons (1855-1944)

- Herbert John Parsons (1857-1948)

Road through Elsfield

During the course of the 19th century increasing urbanisation created a profound nostalgia among the middle classes for the countryside of their childhood where they could perhaps, as Lowe expresses it, “re-create a sense of community and human solidarity from the dislocation and fragmentation wrought by industrialisation”. The bourgeoisie of nineteenth century England, having made their money in industry or banking, began to take on the values of the gentry, where wealth was not the only motivator, but where an appreciation of the aesthetic qualities of the countryside was important and where a love of Nature was presented, in literature at least, as a transcendental experience which fed people’s spiritual needs.

Herbert Parsons who was a partner in the Old Bank in the High Street in Oxford, and who moved to Elsfield in the middle of the nineteenth century may or may not have appreciated the beauties of Nature but he was certainly in love with country living. He and his wife Louisa, moved into Elsfield Manor in the 1850s soon after their marriage in 1851, leasing the property from the North family, who owned the parish but were absentee landlords. Both Herbert Parsons and his wife came from banking families. Louisa was Herbert’s first cousin, having been born a Thomson and the Thomson and Parsons families ran the Old Bank, in the High Street in Oxford, having been associated with it since 1776, when a certain John Parsons, a mercer, teamed up with another mercer, William Fletcher of Broad Street, to provide banking services to their customers. The Thomson family, also living in Broad Street, had a variety of trades including cabinet making and gun smithing. They seem to have become involved in the banking business through marriage and inheritance. In the 19th century much of the bank’s business was with the university colleges but a large part of their personal fortunes came from investment in the Oxford Canal Navigation Company.

Herbert Parsons

Herbert Parsons of Elsfield Manor was the grandson of John Parsons, mayor of Oxford 1788-1809 and the great nephew of the master of Balliol. There was much intermarrying of the Thomson and Parsons families. When Herbert married his first cousin in 1851, he was following his father John’s example for John had married Elizabeth Thomson. Herbert and Louisa’s son was also to follow the family pattern in 1904 by marrying another Thomson, Mabel Mary.

Unsurprisingly, considering his family connections, Herbert was a graduate of Balliol College but seems to have entered the banking profession reluctantly. His father’s diary of 1849 records that he was often late for work, didn’t join in the family prayers before breakfast and if at home in the evening, would often not speak and dozed the evening away. On 4th April of that year his father noted that “Herbert not here till eleven, told him he ought to have been earlier, answered me very improperly”.

Louisa Parsons

Herbert was much closer to his uncle Guy Thomson, the father of his future wife. They were both keen on country pursuits, shooting and going hunting together. His father considered that he spent days “dangling about with the Thomsons”, one reason no doubt being his interest in Louisa.

When he married and moved to Elsfield in the early 1850s he seems to have settled down, becoming a pillar of the community whose generosity was much appreciated. By 1860, the vicar at the time, the Reverend Gordon, expressed that appreciation in a letter to Colonel North, the member of the North family who dealt with Elsfield matters. In a letter concerning the school finances he says that Herbert Parsons, “of whose increasing kindness and liberality to Elsfield it is impossible to speak too highly” will contribute £6 towards the running of the school.

Mary Jane Parsons

In his book The Old Bank, Oxford, Bradburn comments that “the way of life desired by the partners of the Old Bank was that of quiet country gentlemen, and the descendants of the founders achieved this by the middle of the 19th century”. Herbert Parsons certainly fits the bill and between them, Herbert and his wife, through their liberality brought prosperity to the village of Elsfield, in many respects rescuing it from what it had been: a downtrodden collection of cottages straggling along the road, described in a document drawn up for the North family in 1825.

The two Parsons children were born at the Manor, Mary Jane in 1855 and Herbert John, known as John, in 1857. Mary Jane seems to have spent her whole life largely within the confines of the village, being educated at home while her older brother went away to school, though having finished his education, he too joined the bank. John lived at the Manor until he married in January 1904, when the school children were given a day off and all the village invited to see the wedding presents.

Improvements in Village Life

Social historians make the distinction between an ‘open’ and a ‘closed’ village. The ‘open’ village is one where the land is freehold and the freeholders control the development of the village. A ’closed’ village on the other hand is one where the principal landowner controls such factors as where houses can be built and who can live in the village. The inhabitants of closed villages were generally more prosperous than open villages because there was more job security, though not security of tenure of the houses they lived in. There was also often a paternalistic occupant of the ‘big house’ who would keep an eye on the welfare of villagers.

Elsfield shows some of the characteristics of a closed village, since the land was owned by one family, the Norths. However, with an absentee landlord, Elsfield had none of the advantages which a closed village has. There was no wealthy lord of the Manor to dispense gifts and oversee the welfare of his employees. Nor did it have the advantages of an open village where land was available to be bought and built on and where people could use their initiative to develop a business or extend their premises.

From the time when Herbert and Louisa Parsons arrived in Elsfield, the village found itself with occupants of the Manor House who took an interest in the welfare of the inhabitants, provided gifts at Christmas and paid regular wages. Between 1862 and 1877, Herbert Parsons bought Forest Farm, which was outside the parish and when the agricultural depression was in full force in 1886 bought the whole estate from the Norths.

A pump installed by Herbert Parsons in the Manor yard

One of the matters Herbert Parsons turned his attention to was the water supply. To ensure a constant supply of water Herbert Parsons had a reservoir built and installed pumps throughout the village, about one pump to three or four houses, two in Manor yard and two in the house. The farms had their own supplies. Saturday evenings were busy times as the men fetched water in buckets slung on yokes to fill the coppers for washing. The pumps were wrapped with straw at the first signs of frost, to prevent them from being frozen and were still in use until piped water was installed in the late 1940s.

A common way of measuring the health of a community is by studying the mortality rate of young children and babies. In the decade 1841-1851 there were 22 deaths of children between the ages of nought and fourteen. This dropped in the following decade to ten and continued to fall until in the last decade of the century it was only four. The health of Elsfield residents therefore had significantly improved over the second half of the 19th century. Was this due to the installation of pumped water? If it is apparent that children were dying of diarrhoea and water borne diseases, then Herbert Parsons’ water pumps would be life savers. Or was it due to improvements in the supply of food, since the twenty years from 1850 are considered the high point of English agriculture, which brought great prosperity for farmers and, as a consequence to their workers.

National studies have shown there were two danger periods for small children: in early Spring from respiratory diseases and in late summer from diarrhoea. This double peak does not show up in the Elsfield statistics, suggesting that the lack of pure drinking water was not the cause of the higher number of deaths. It seems likely that the improvement in health was due to better food.

The reason for the prosperity of farming, with agricultural production increasing by 70% was due to several causes. New types of cattle feed had been introduced, notably oilseed cake which meant cattle could be fattened up during the winter months. Drainage was improved, giving more cultivatable land. The earliest methods of draining fields had involved cutting either parallel or herringbone patterns of ditches across enclosures and packing them with brushwood or stones. Drain pipes were invented by John Reade in 1843 and the mole plough[1] by John Fowler in 1859, which must have been a great help in farming in Elsfield, since much of the low-lying land was very wet in winter. The first artificial fertilisers were invented by John Lawes in the 1840s: phosphate of lime, sulphate of potash, salts of magnesia and superphosphates, which greatly increased the yields. There was also a ready market for agricultural products due to the increase in urban population which ensured a steady market for agricultural products and increased access to markets via the railways, canals and a better road system.

There were three farms which appear to have been functioning as independent entities, the farmers leasing their land first from the Norths then after 1886 from Herbert Parsons: Home Farm, Church Farm, and Hill Farm. In the latter part of the 19th century Sescut Farm, down by the Cherwell and outside the village itself, and Forest Farm, the last house along the village street, were used to house farm workers, the cowman living at Forest Farm.

Geraldine Blanchett

An important source of information about Elsfield at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century is Ethel May Allam. Her recollections were recorded and published in a local history magazine Top Oxon. by the wife of the vicar of Islip, Geraldine Blanchett, herself the daughter of the one-time vicar of Elsfield, the Reverend Elkington. Ethel May had been born in the village and had been employed at one time as teacher of the infants at the school. Her father, William Elston, had come to the village as a groom at the Manor and had married Harriet Gammon, daughter of the local wheelwright and carpenter, Moses Gammon. Ethel May recalls that Mr Parsons sent his men with wagon and horses to fetch coal from the canal barges and that it usually ran to two tons of coal per cottage.

William Elston

Mr Parsons kept a herd of cows which were milked morning and night. Two large buckets of milk were taken to the dairy and placed in pans for the cream to rise. These were skimmed and the cream was saved for butter which villagers were allowed to buy every Wednesday and Saturday at a shilling a pound. Making the butter was hard work. It took two hours of churning before it could be potted up and weighed, then all the equipment, the milk pans, the separator, the strainer and the milk buckets had to be scalded to ensure they were spotless.

The skimmed milk was given out every morning at eight o’clock and the children fetched it in cans. The housekeeper and cook, Mrs Huxley, was prompt on time, said May Allam, and she was not pleased if anyone was late and had to fetch her to the dairy again. Mrs Huxley is listed in the 1901 census as a cook, aged 58, from Flint.

There was a strict hierarchy among farm workers, with the men who worked with animals being above the farm labourers so the head dairyman and the head horseman would be paid more than others. In 1905, a horseman in Oxfordshire could expect to be paid between 14 and 16 shillings a week. A worksheet from the estate survives from 1901, towards the end of Herbert Parsons’ life. At this time there were 49 people working for him. In the week ending 4th January the carter’s work consisted of taking straw round to the various farms, carrying hurdles, litter, chaff and straw, for which he was paid 2s 2d a day. He made up his six day week by thrashing, to take home 13s 6d, rather less than the national average. The carter had a very long working day, having to be up at about four in the morning to groom, feed and water the horses ready for them to start working at seven o’clock. The carter’s day also finished after the other labourers’ because when the horses had finished working they had again to be groomed, fed and watered.

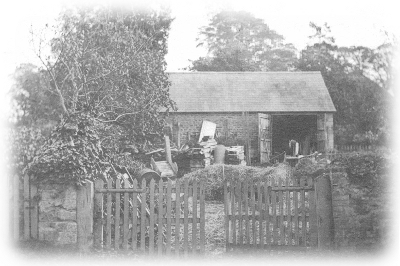

Carpenter’s workshop alongside Tree Cottage

In that week fifty- four man days were spent on ploughing, 23 on thrashing, 30 with the sheep, 32 with dairy and beef cattle and unsurprisingly, given the number of animals, 30 days spent with dung, loading it into the dung cart, taking it to dung heaps, moving it, spreading it. There were seven days spent going to and from Oxford, taking corn and bringing coal.

As well as the farm workers Herbert Parsons also employed R. and F. Allum as carpenters, one paid 3s 4d a day and the other, presumably an apprentice, paid 2 shillings for a six day week. The mason, Mr Smith, also had a family member with him, paid 1s while he earned the rate for a skilled man, like the carpenter, 3s 4d. The smith also belonged to this higher earning group while the keeper was paid only 2s 2d, like the labourers, and his boy was paid 10d.

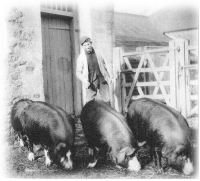

Pigs

A stock list from 1912, shortly after Herbert Parsons’ death, shows that there were 481 sheep of varying ages, 69 cattle within the parish and more kept on land owned by the family outside the parish at Stowood and Folly Farm, at Gurdon’s Ground a family of pigs consisting of sow, boar, six little pigs and eight feeding pigs. The horses are listed by name: Captain, Rose, Violet and so on, thirty-five in all, with nine being kept at Lodge Farm, again outside the parish.

The estate remained in the Parsons family until 1919 though Herbert had died in 1911,and an estate labour sheet for the week ending 17th January when Herbert John, son of Herbert and Louisa, was managing the estate, shows a much less flourishing picture than that conveyed eighteen years earlier. The devastation wrought by the war is evident in the fact that the manpower to run the farms had halved. There were now only 25 people employed on the land three of them women who were paid 2s 6d, half the pay of the men who were now earning 5s or 5s 4d a day. One difference was that 4d a week was deducted for health insurance, which may account for the days now noted as ‘ill’ rather than absent, as in 1901. Colwell, the shepherd, was ill for the whole of that week and was paid 2s 6d for three of the five days he was ill. It is likely, too, that the large number of horses used in 1901 had been seriously depleted, since horses were used and died in large numbers on the battlefields. After the war they were sold off or, if too old or ill, shot. The number of days spent ploughing was reduced to 23 while thrashing took up 18 man days.

Throughout much of the 19th century some parishioners rented garden plots to grow vegetables which would supplement their meagre wages. An agreement between Richard Lock and Colonel North dated 10th October 1840 shows that the yearly rent for such a plot was five shillings paid quarterly. There were various conditions attached to the agreement: that the ground should be dug but not ploughed; that half the plot should grow wheat and the other vegetables; that the crops be rotated annually and that the ground be manured twice a year. The person renting the land was not allowed to sell what he produced. It had to be for his own use and he was not allowed to be drunk on the land. Richard Lock’s plot was number 18, so there must have been a substantial amount of land made over to garden plots. A later agreement between Colonel North and Joseph Lock on 1st July 1872 has the same terms but the rent has now doubled to ten shillings.

Gleaning

A further addition to the household income was from gleaning, which women and children in the village were allowed to do when the harvest had been gathered in. The gleaned corn would be bound into miniature sheaves and dropped into the linen bag carried by many of the gleaners. The corn thus collected would be added to any which the family had grown in their allotment and stored until it could be threshed. If the family had a pig or poultry they might be fed on the gleanings, but otherwise it could be ground into flour.

[1]A plough which can make an underground drainage channel.

Servants

While farming provided work mainly for the men in the latter half of the 19th century, women and girls found employment in domestic service with the farmers, the vicar but above all with the Manor. The number of servants employed in a household was a mark of social standing. When Seebohm Rowntree conducted a survey in York into poverty in the city in 1899 the dividing line he used between working- and middle- class was the employment of a servant. It was estimated that a minimum of three servants were needed to ensure the smooth running of a household: a cook, a housemaid and a parlourmaid or nursemaid if there were small children in the family.

Using this criterion, Herbert Parsons and his family were very firmly middle class. When he moved into the Manor, in the 1850s he employed seven servants, which later rose to ten. By 1901, he was employing eight live-in servants, though these were not people from Elsfield village as Elsfield girls would often go into service in other villages. This was a common pattern with girls being sent at least twenty miles from home for a number of reasons: to stop girls running home, to discourage followers and to make sure they could not gossip about their employers to anyone in the locality.

The first record of the servants the Parsons employed dates from 1861, by which time their children were aged six and three. They were employing a lady’s maid, a cook, a nurse, and a nursemaid thirteen year old Harriet Gammon, who was a local girl. They also employed two men servants, a butler and a groom, William Elston. The nineteen year old kitchen maid and the cook, had been born in Bolden, where the Parsons lived prior to their move to Elsfield, so it is possible they had been employed by the Parsons prior to the move. Having a butler was a mark of high social standing, as it was expensive to employ a manservant. Not only were men paid more than women, but there was a tax levied on the employment of a manservant. This had been introduced in 1777 by Lord North to help pay for the American War of Independence and while in the course of the 19th century the tax on male servants was substantially eased, it was not finally abolished until 1937. There is no record of the appearance of the Parsons’ butler, but a tall man, over 5 ft 10 inches, could command a higher salary than a shorter man. The Parsons employed two butlers between 1861 and 1901. In 1861, their butler was a young Wiltshire man, James Chambers but he had been replaced by 1871 by 37 year old Londoner James Barratt who remained with the family for over twenty years.

One of the responsibilities of the butler was brewing the beer, which was undertaken in one of the substantial outhouses constructed by Herbert Parsons. The smell permeated the whole village when brewing was taking place. Another responsibility was the wine, not only decanting it for daily use but keeping a tally on what had been drunk. In larger households, the butler also had to fine the wine. This was a process by which a cask was cleared of impurities by adding, according to Mrs Beeton, isinglass, gelatine or gum Arabic. Whatever was chosen, it was stirred into the wine and the bubbles were skimmed off as they rose to the surface. The mixture had to stand for three or four days before it was ready for use. A further responsibility for the butler was checking last thing at night that doors were locked, windows made safe and that fires were out.

Elizabeth Clarke

By 1871, Mary Jane Parsons was aged sixteen, had acquired a governess, 23 year old Clarissa Berwick, from Kent, and her brother Herbert John, aged now fourteen, was away at school. To ensure the smooth running of the household there was now a cook, a different one from ten years previously, Elizabeth Clarke, who is listed as a housemaid, but who stayed for many years with the family and is described by Ethel May Allam as a housekeeper. Helping the cook and housekeeper were two under housemaids and a kitchen maid. Completing the household were James Barrett the butler, a footman and a groom. Harriet Gammon, who had been a nursemaid at the Manor when the children were little had left the village, though she was to return later and become the second wife of William Elston the groom.

In 1901, nine years after Louisa’s death, there was no lady’s maid, so Mary Jane, now aged 46, obviously did not feel the need for one. John, her brother, now aged 43 was still unmarried and living at home. To look after the three of them there were Elizabeth Clarke, who is still listed as a housemaid, and Alice Huxley the cook. Also living in were a kitchen maid, a scullery maid, a housemaid, a laundry maid, a footman and a groom, none of them from Elsfield. Elizabeth Clarke lived in Elsfield until her death in 1914 aged 88.

Supporting the Poor

We have seen that the Herbert Parsons was prepared to give £6 a year to the school. A more official responsibility was the tax paid by the prosperous members of the community to provide for paupers. This was not new. According to the parish records, 1800 was a ‘dear’ winter, when the better off people of the parish contributed £25 6s to support poor members of the parish, the money being spent on coals, potatoes, flannel petticoats and waistcoats.

In 1862, it was the three farmers (John Greaves at Home Farm, William Parsons at Hill Farm and William Tredwell at Church Farm), Herbert Parsons at the Manor, the Reverend Gordon, and Colonel North, the landowner, who paid poor rate. The levy was one shilling in the pound of the rateable value of their property, linked to the amount of land they owned. Colonel North paid only on the property and land which was not rented out so his contribution was less than the others. He paid for a barnyard, an allotment and a wood, all of which covered 24 acres. The rateable value for this property was £18 so he paid 18 shillings poor rate twice a year. The vicar paid £4-16-0d, Herbert Parsons paid for the Manor and accompanying land and extra for Gardener’s Cottage. He contributed £3-4-0d in all. The farmers contributed the most with John Greaves paying £17-16-0d, William Parsons £18 and William Tredwell £20-5s.

The rate increased in 1865 with the second payment being two shillings in the pound. By this time Reverend Gordon was renting a field from Col. North, still known as Vicar’s Field, as well as his house and he paid poor rate on that in addition to the house. There were 29 cottages the inhabitants of which paid £6-0-8d between them. In 1842, two guineas for maintenance and almost £26 in out relief were paid out in the village, thus showing that the poor of Elsfield were generally maintained in their own homes rather than in the workhouse.

Philanthropy

As well as direct taxes to support the poor, the village gentry, consisting of the three farmers, the vicar, the North family and Herbert Parsons all paid into the Coal and Clothing Club, started in 1835 possibly by, the Reverend Gordon. This was a kind of savings club where members paid a fixed amount every week with their savings being topped up by the local gentry. The accounts for 1874, the 39th report of the club, are as follows:

| 25 members | £34-9s |

| Colonel and Lady North | £5 |

| Mr and Mrs Parsons | £3-3s |

| Rev. and Mrs Gordon | £1-11-6d |

| Mr and Mrs Greaves, Home Farm | 15s. |

| Mrs Colcutt in memory of her father | £1 |

The money was shared out between the 25 contributors in December. The money was collected from the villagers perhaps first of all by the Reverend Gordon, but certainly in the 20th century by Mary Jane Parsons, who, according to Susan Buchan kept the money in calico bags in her desk.

In the previous year, 1873, two of the farmers, William Parsons and William Tredwell, had stopped donating anything to the Club. The Reverend Gordon ‘s letter to Col. North, which accompanied the Statement from the Coal and Clothing Fund drew his attention to the fact that it was “not so good as last year. I regret to say that this is not the only or the greatest evil that the mischievous labourers’ Union has brought into this hitherto most peaceful and well-to-do parish – the very last it should have touched.” (He is referring to the National Agricultural Labourers’ Union, founded in 1872. Their aims were to improve wages and limit working hours. Some farm labourers worked an eleven hour day six days a week.) Colonel North replied that he was sorry to see Mr William Parsons and Mr Tredwell no longer subscribe. “I know they were very much hurt and annoyed at the charges brought against them without any foundation and with the gross ingratitude they have met with with regard to the required alterations at the school.” This is a reference to the fact that the community had had to expend money bringing the school premises up to scratch because of the 1870 Education Act. The Reverend Gordon and the rest of the village gentry were afraid of the government setting up a Board school, when they would have lost control of the curriculum. The Reverend Gordon worked extremely hard to make sure the school remained under local control and that it stayed a Voluntary school where the Church would maintain control over what was taught. Money had to be spent on bringing the premises up to a certain standard. The floor had to be boarded, they had to ensure that the lighting, heating and ‘offices’, as they delicately called the lavatories, were adequate. They also had to enlarge the school room by incorporating a blacksmith’s smithy, which up to 1873 was making the teacher’s working conditions considerably more difficult than they need have been.

Both Mrs Parsons and her daughter were involved in supervising activities at the school, especially the sewing, which attained a high standard. Mrs and Miss Parsons visited the school each week and kept it supplied with sewing material. They helped the girls with their sewing, provided the material for pinafores, and gave them to the girls when completed. Mrs Parsons was a member of the Oxford Ladies group which organised prestigious events such as the first Prize Needlework Exhibition in 1877, and her daughter carried on her interest in embroidery throughout her life, ensuring that the girls at Elsfield school had a high level of sewing skills.

In the last years of the 19th and the first years of the 20th century Miss Parsons was caught up in the enthusiasm for traditional country life which many people felt was on the verge of extinction and which resulted in a revival of such phenomena as Morris dancing. Miss Parsons was not immune to these ideas and was in a position to translate her ideas into action. She gave a maypole to the school and folk songs and Morris dancing became part of the school curriculum.

Direct Gifts

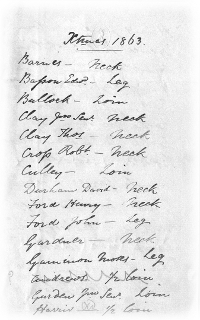

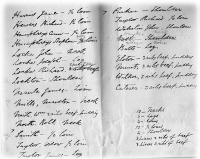

Mrs Parsons’s Christmas list

The Parsons family gave generously to their employees. There were presents of either clothing or food, the bulk of them given at Christmas, though summer clothing for the children was also provided, and these may have been given out in time for the May Day celebration, or Whit Sunday.

In winter, the boys were given cloth which was made up into suits by Mrs Elston, Mrs Allam’s mother. They were also bought a cap ordered at Lane’s shop in Oxford where the parents took their sons to be fitted. In winter, the girls received a hat, coat, red scarf, and cut-out dress in black and red check and in summer a pink and white check gingham dress and straw hat trimmed with red ribbons. Elsfield children would thus be immediately recognisable if they ever ventured into the outside world, as residents of the Parsons’ village.

Mrs Parsons’s Christmas list

Sometimes there were casual gifts of food to the poor of the village, with Mrs Allam recording towards the end of the century that Sarah Clay was given used tea leaves from the Manor. This was not such a sign of poverty as it seems today but rather a hangover from a time when tea and sugar were very expensive in the first half of the 19th century. It was the regular practice then in many households for the tea leaves which had been used ‘upstairs’ to be re-used in the servants’ quarters.

Food was given out at Christmas, and it is fortunate that a list compiled by Mrs Parsons or her housekeeper in 1863 survives. The meat is likely to be pork or mutton since beef is listed separately, and it is likely that the gifts were linked to the social hierarchy of the village with the more important people being given the better cuts of meat.

The presents Mrs Parsons gave in 1863 to villager

| Barnes | Neck | Basson | Leg | Bullock | Loin | Clay | Neck |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clay Snr | Neck | Bullock | Loin | Culley | Loin | Ford, John | Neck |

| Durham | Neck | Cross | Neck | Ford, Henry | Neck | Humphreys | Loin |

| Gardener | Neck | Gammon, Robert | Leg | Gurden | Loin | S. Locke J. | Leg |

| Harrier | Half loin | Harris, Jane | Half loin | Hewers | Half loin | Locke R | Shoulder |

| Humphreys | Half loin | Locke | Neck | Taylor (widow) | Half loin | ||

| Lockton | Shoulder | Maule | Loin | Mills | Neck | ||

| North | Neck | Smith | Half loin | Taylor | Half loin | ||

| Taylor | Leg | Parker | Shoulder | Wakelin | Shoulder | ||

| East | Shoulder | Butts | Leg | Elston | 3 ribs beef and pudding | ||

| Munt | 3 ribs beef and pudding | Walker | 2 ribs beef and pudding | ||||

| Caterer | 2 ribs beef and pudding | North | 2 ribs beef and pudding | ||||

Social Life

Herbert Parsons did not abandon his love of hunting when he moved into Elsfield Manor. Ethel May Allam recalls that on hunting days, the hounds met at the Manor where a supply of sandwiches and beer was distributed by the butler and his footman to the huntsmen on horseback. The ladies and the runners were given food in the servants’ hall , the home-brewed beer being served by Mr Barnet, the footman, and later by Mr Webb, who later became chauffeur to John Buchan. The Stable Yard with its horse boxes was filled with hunters and carriage horses, grooms and coachmen. The farmers in the village may not have been pleased at the damage wreaked by the hunt as they galloped across fields of corn or leaped fences and hedges. They would have been instructed not to use wire fencing, a cheap alternative to the traditional hawthorn, and anathema to the hunting fraternity, even before the invention of barbed wire in the 1880s. Nor would they have been allowed to shoot foxes, even if they did carry off the poultry.

Shooting was also a regular pastime in the autumn. Herbert Parsons seems to have had scant regard for the education the school provided since he regularly took older boys out of school to act as beaters. Vermin such as stoats, weasels, polecats, magpies, crows and hawks would be killed by the gamekeeper to preserve the partridges and pheasants to be shot by Herbert Parsons and his friends.

Village Celebrations

Ethel May Allam’s recollections of village celebrations seem to have concentrated on Easter, May Day and Christmas. In all of these the Manor played a crucial role, being the focus of much of the acitivity.There is no mention of Bonfire Night, though it is difficult to believe that this was not celebrated, given the rural nature of Elsfield. Like many oral accounts, the actual dating of the events remembered by Mrs Allam is vague. Her description of May Day must be later than 1905 because in that year she started her work with the Infants class.

May Day

May Day, 1909

One of the villagers, Miss Narroway, would make a garland composed of three large, thick sticks tied over the top and fixed with three sizes of hoops. She was paid one shilling for this. A few weeks before May Day Miss Parsons would look out for a branch of May and would place it in her greenhouse for it to be in bloom when it was needed.

Flowers would be fixed to the garland and the branch of May would be fastened on top. There was a banner of red sateen lettered with white braid, saying “May Day” and the date (the figures were altered each year). This was carried by two boys. Four girls carried the garland and the May King and Queen attended.

Meeting at the School with the teacher, Miss Elston, later Ethel May Allam, they marched first to the Manor House, going round the garden, where each was given a red geranium, pinned in place by Miss Parsons. Afterwards they visited each house in the village with the garland and a collecting box, going to each front door. Takings usually amounted to about 10d a child. They then returned to the School for a grand tea at 4 p.m., followed by games and swings in the field. Before leaving each child was given a ball.

The song they sang was:

Tis the first of May. We are happy and gay.

And at your door I stand.

Turn your heads not away but with us be gay

Because it is now May morn.

A bunch of May I have brought to you

And I can no longer stay

God bless you all

Both great and small

And I wish you a merry merry May.

Christmas

The head gardener at the manor, Mr Gould and his staff, and in later years when Mr Gould had retired, Mr Morbey and his son cut holly, ivy, box and yew for the Church Decorations. The wreaths and texts were made at the School: bunches of small everlasting flowers were placed in the wreaths and the texts such as “Unto us a Child is Born” were made of holly leaves and berries. After 1919, when the Manor had been sold to the Buchans and Miss Parsons had moved to Home Farm, the wreaths were made in Miss Parsons’ kitchen. Susan Buchan comments that Miss Parsons had a Victorian love of lavishness and that parts of the church almost sank under swathes of greenery and holly at Christmas and mounds of primroses and moss at Easter.

While the Parsons family were living at the Manor, a large Christmas tree for the children was placed in the Manor House dining room. The tree was decorated and all around the room were table places for the children with presents for them and a drink. Tea was served first and before going home they sat down again for refreshments. On the table were two large iced cakes with tiny china animals. Each child was presented with a china animal, a slice of cake and an orange to take home.

After 1919, when she had moved to Home Farm Miss Parsons continued to give the Christmas party for the children at her house. Mrs Buchan and her children, now resident at the Manor, handed round the food, which disappeared very quickly and after tea the children proceeded to the drawing room when they sang all the carols they knew in a shadowed room lit by candles and oil lamps. Tea for the adults was served at small tables with a splendid Victorian teapot and urn then everyone walked down the hill to the school house where the Christmas tree had been erected.

When the Parsons lived at the Manor, Mrs Allam recalls that on Christmas Eve all the children were given presents and Christmas cards. Householders received sheets, blankets, dress lengths, and calico as well as the joint of meat for Christmas dinner.

Easter circa 1910

On Good Friday, the children met at the Manor House after Morning Service. They were given baskets and a ball of wool and were escorted to Stow Wood by the gardener, Mr Gould, to pick primroses. These were for decorating the Church. On returning each child was given a bun .After Morning Service on Easter Day the children collected at the front door of the Manor for buns and oranges.

For the decorations at the Church, as at Christmas the gardeners cut evergreens, ivy, box,and yew. This was taken to the School where wreaths were made with the help of laths, iron and string, which took a whole day. Texts on boards were placed over the door and archway, with the message “Christ is risen” spelled out in everlasting flowers.

Building works

The Victorians were great builders and modifiers of old buildings, and none more so than Herbert Parsons. A vicarage had been built in 1836 before he came to Elsfield, to house the Reverend Gordon and his family. The house, situated next to the church, had been paid for by Lady Susan Doyle, a member of the North family, who gave £800, and the foundation stone was laid by the Reverend Gordon’s two children, Henry and Mary.

The Church

When they arrived in the village, Herbert Parsons and his wife spent considerable amounts of money on the church. It was remodelled in 1849 and 1859 when it was restored to a very complete Early English appearance. The Jacobean pulpit and the 12th century tub font were retained. The churchwardens’ accounts reveal that in 1859 there was a minor restoration by G.E Street (re-flooring and re-seating) which cost £413-11-0d. Contributors to this were Colonel North, who paid for the communion rail to be made up from 17th century balusters at a cost of £50. John Parsons (Herbert’s father), Herbert Parsons and Miss Parsons (Herbert’s sister) all contributed £25 each while William Parsons and William Tredwell, both farmers, paid £15. Mr Greaves, one of the church wardens, paid £10, the Diocesan Society £50, the Incorporated Society for the Propagation of the Gospel paid £56 while the Vicar and his friends contributed a magnificent £126-19-1d. The collection at the re-opening ceremony also raised £56-11-11d. Herbert’s father noted in his diary that on 7th July 1859 at the opening of the church “Our party went. Herbert gave a great entertainment to ‘Rich and Poor’. All went well.”

Herbert’s wife Louisa donated generously in her own right, in 1860 giving a silver communion service consisting of flacon, chalice, patern and alms dish and an altar cloth. At some time in the 1870s or 80s she also paid for a mosaic of the Last Supper by Salviati, which decorates the wall behind the altar. Salviati was a very popular artist in Victorian England. There are Salviati mosaics in St Paul’s in London, the Albert Memorial, St George’s chapel in Windsor. In America there is a Salviati mosaic in the Baptistry Chapel of the Church of St John the Baptist in New York City, and one of Abraham Lincoln in the Senate House in Washington, so it is quite a surprise to find one of his mosaics in this simple village church.

The church was kept spick and span by the cleaning lady, Mrs Wakelin in 1866, who was paid £1 a quarter. Mrs Lockton had taken over the responsibility in 1883 and Mrs Narroway in 1901. There was no change in their wages, but by 1901 £2-12-0d was being paid to the clerk with an additional £1 for attending to the fires.

The Manor

The Elsfield Manor

The Manor House was more than doubled in size by Herbert Parsons. The High Gothic Victorian addition sits incongruously alongside the 18th century building but must have provided a great deal more accommodation for his family and servants. His study window was next to the road and he is reputed to have watched in the mirror which hung above his desk, to see who in the village had gone down to Marston to the pub. The farm labourers responded by removing their boots so they could not be heard as they passed the Manor on their way home.

Herbert Parsons in his old age in his pony carriage